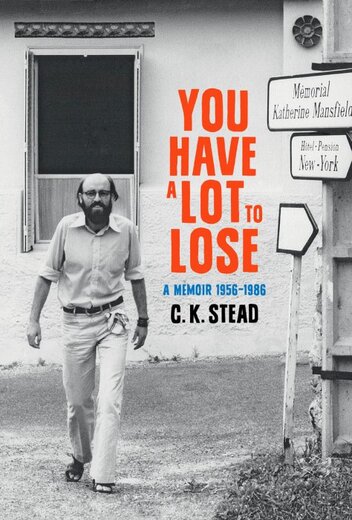

by C. K. Stead

Christian Karlson "Karl" Stead was born in Auckland. For much of his career he was Professor of English at the University of Auckland, retiring in 1986 to write full-time.

Widely honoured as a ‘titan of NZ literature’, CK Stead’s writings include poetry, short stories, novels, literary criticism and editing as well as a brief statement written on the wall of a Hamilton police cell in the wake of his arrest during the aborted Waikato-Springboks game of 1981.

He has been honoured at many levels: by his contemporaries in a lengthy list of prizes and awards for literary achievement that includes the Katharine Mansfield Menton Scholarship, the Montana Prize for poetry and the highly-regarded Sarah Broom Poetry Prize. He has been honoured by governments of both colours in the award of the Prime Minister’s Award for both Literary Achievement and Fiction; the Queen’s Medal then a CBE for services to New Zealand literature and, in 2007, membership of the Order of New Zealand. In 1995 his contribution to the international world of literature was recognised in his election as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, while in August 2015, Stead was named the New Zealand Poet Laureate for 2015 to 2017.

Stead’s claims to ‘titanship’ are therefore well established, for in both range and number, his literary output almost mocks the term ‘prolific’. Of the corpus of nigh on forty substantial works following his academic foundation stone, ‘The New Poetic’, many are written in consecutive years but none except for ‘The Singing Whakapapa’ is separated by more than two years from the preceding one.

With reference to his literary upbringing “The University of Auckland” writes Stead, “. . . first educated me, then employed me . . .” and his association with it involved him in the world of those giants of a distinct, if inchoate, NZ literature: Duggan, Baxter, Curnow, Shadbolt, Frame, among many others and, over and above all, in the strength of his friendship with the Godfather-like Frank Sargeson. One notes, in passing, that this was also a world of Renaissance-type involvement with plays, opera, concerts, music and the art of McCahon and Henderson, and is redolent of a time when “education” was concerned with more, perhaps, than today’s Google-dependent linearity.

There is, though, a sense in which if it didn’t happen in Auckland, it didn’t happen; an example is a Sargeson-like nod towards the writing of Ronald Hugh Morrieson that acknowledges the rural voice without mentioning Hawera, where Morrieson lived, worked and died.

Stead’s doctorate was undertaken at Bristol and, in the milieu for literary criticism established by his supervisor there, LC Knights and by FR Leavis of Cambridge, he learned to take no prisoners, and this has been seized on by his detractors. Indeed, Diana Wichtel once quoted Frank Sargeson as saying to Stead, “I can’t imagine a worse fate than to be reviewed by you.”

In his later years Stead himself acknowledged the truth of this, but in his defence, if one were asked to choose only one salient feature of this memoir, for me it would be Stead’s total dedication to the literary world and all facets of it. In this sense, a thing ‘is’ or it ‘is not’ and it is never Stead’s way to encourage doubt whether reviewing, critiquing, editing or travelling across the world on the literary scent regardless of anything else.

He is as ruthless with himself and his failings, though, as with any writer he reviews. In his recounting of his own moral shortcomings, and in particular of two bouts of marital infidelity, we see his conviction not only that the truth is unflinchingly valid but a dedication to a ‘warts and all’ picture that would earn a nod of approval from Cromwell himself. By the same token, that honesty of conviction underpins his views on the treatment by their own society of Australian aborigines, the Vietnam War and the Springbok tour of 1981.

So what does this, the second of his memoirs, reveal of Christian Karlson Stead? Growing up in a NZ suspicious of anything that didn’t conduce to the battle for world rugby hegemony against the Springboks, his early yet enduring commitment to a NZ literary nationalism contrasts oddly with a discernible homage to the academic world of the UK; one (he notes) in which the Commonwealth nations were “clamouring to be free” but “seldom wanting complete severance”. He is revealed as a good friend to the wide network of contacts, colleagues and acquaintances with whom he maintained a truly impressive correspondence. Never one to hold a grudge, he participates in the cut-and-thrust of literary criticism on the basis of an unvarying ethic that “Business is business”.

Turning to the book itself, one or two infelicities that may perhaps be whimsical bons mots are revealed on pages 164 and 165 where Stead writes of a “. . . priests’s surplus” and of the “Security Intelligent Service”. More important, however, is the omission of an index that would greatly assist the to-ing and fro-ing involved in keeping up with the vast network referred to in my preceding paragraph, and this omission is the more surprising given Stead’s scrupulous footnoting throughout.

Overall, ‘You Have a Lot to Lose: a memoir 1956-1986’ is an important look at a seminal period in New Zealand’s literary history through the eyes of one of its great movers and shakers.

Author: C. K. Stead.

Publisher: Auckland University Press

ISBN: 9781869409128

RRP: $49.99

Available: bookshops

RSS Feed

RSS Feed