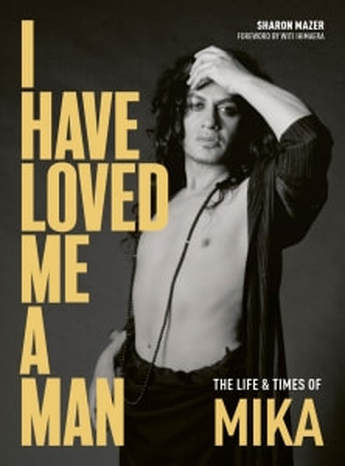

I Have Loved Me A Man: The Life & Times of Mika

by Sharon Mazer

with a Foreword by Witi Ihimaera

The author is an academic specialising in theatre and performance studies, and, as stated in the publisher’s explanatory publicity, in this book she ‘takes readers inside the social revolution that has moved New Zealand from the 1960s to the present day through the story of…gay Māori performance artist: Mika.’

Adopted at birth into a Pākehā family, Neil Gudsell, later Mika, is the natural son of a Pākehā mother and a Māori father. From an early age he knew that he was gay, and embraced that knowledge. Somewhat later, he discovered his Māori heritage, and that, too, he embraced with enthusiasm.

As an openly gay Māori adolescent in Timaru in the 1960s and 70s, it might be expected that his life would have been a constant struggle against prejudice and worse, but from the beginning Mika seems to have had an abundance of insouciant self-belief as well as considerable physical strength and athleticism, and thus was able to be what he is without disguise and only minimal overt hostility directed against him.

Later, in Christchurch, Mika (still Neil Gudsell at this stage) developed his physical and artistic skills through aerobics, jazzercise and various types of dancing, and from this base he established a career as a performer, and, for a time, as a television and movie actor.

With the support of others, such as Carmen and Dalvanius Prime, Mika developed his own style typified by an exuberant physicality and sexuality, and was soon directing, dancing, singing and generally starring in a series of performances in New Zealand and overseas, particularly at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. There was always a political edge to these performances, a deliberate fostering of Gay Rights and Aids awareness, and they also incorporated the imitation of aspects of traditional Māori ritual, stylised Māori or Pasifika costume and set design and the use of props such as taiaha.

Mika’s idiosyncratic interpretation of Māori culture was not always welcomed by Māori traditionalists, nor did his ‘camp’ style have much appeal to those who saw it as something quite distinct from ‘high’ art. But, as the author notes, Mika is a performer, a ‘quintessential showman’, whose whole approach challenges any such distinctions. The author describes Mika’s performance art as ‘postcolonial camp’, and as such, as being ‘celebratory but not utopian, political without being prescriptive, and critical without losing its sense of humour.’

To some, the major interest in this book will be in the author’s analysis of the ways in which New Zealand society’s attitudes to matters of sexual identity and race have changed since the sixties. Others will be more interested in Mika the performer and the man. But an attempt to identify Mika is something like trying to shape a recognisable figure from quicksilver. Clearly there is something protean about him, just as there is about his performances. Perhaps the most identifiable trait is his empathy with young people, particularly Māori and Pasifika, who are struggling to establish a personal identity. In this regard, he has established a Trust with the mission to ‘ignite young minds and transform bodies towards better lives through the performing arts and physical culture.’

The book is copiously illustrated with photographs from Mika’s own collection. Some of these are decidedly uninhibited, but that is Mika’s style. As Witi Ihimaera says in his Foreword: ‘He’s still fabulous… Still a star.’

Whether your main interest is social history or the career of Mika himself, this is an absorbing read.

Author: Sharon Mazer

Publisher: University of Auckland Press

ISBN: 9781869408862

RRP: $59.99

Available: bookshops

RSS Feed

RSS Feed