by Vaughan Rapatahana

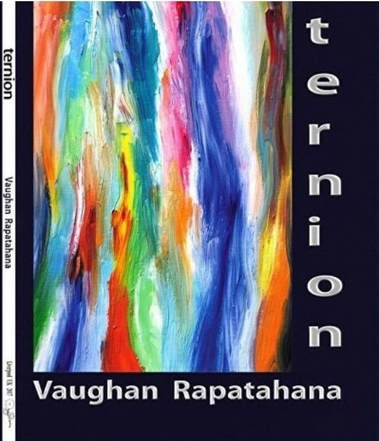

The cover leads the reader into any book. This cover, with its ribbons of vivid colours that stream both up and down, yet never seem to mingle, presents an apt context for the poems.

Overall, on first read-through, I felt I’d been hurtling down a busy highway in some alien place, picking up only random, disconnected signs as they flashed by, some in a language I didn’t recognise. Discordant, cacophonous, unruly, a sprawling city of symbols and sirens.

The editor has chosen to begin with death. New life evokes old death, in ‘Blake’. The blank, final gaze of a corpse mirrored in the static slices of life on the wall. Chilling.

For me, ‘my father’s death’ with its plethora of double adjectives, over-does the emotion, descending into cliché with ‘pearly gates’, though I like very much the final word ‘limn’. I paused in ‘park plaques’ to try to allow an umbilical cord that conjugates us all from within the group, but failed.

In ‘endgame’, not knowing who ‘you’ addresses, I’m unable to run the images together into coherence. ‘I carry a rage’ delights me with its sound-play: conniption, Wittgenstein, submission, and mis interpreted. In ‘the rain’ the poet recognises himself, coming out of his safety zone, his ‘house’, to identify with the rain, as a ‘dirty old man’.

I like the use of direct speech in ‘waharoa’, offered ‘like a dirty lolly’. From such brief, personal exchanges, an image of loss that’s universal, yet unvoiced.

In ‘rua kenana century’ many of my concerns about many of the poems appear, so I’ll address them all here:

1. The bold underlining of the poem titles separates their meaning from the poem. This feels like an odd alienation, as more usually, poem titles work together with the text.

2. White space works better on an online page, where the constraints of page and font size, and the ratio between them, are not the same. Here, and in many of the poems, the different fonts and their sizes, the use of bold and underline, italics, translations, and footnotes that aren’t clearly divided from the text of the poem, all combine into a messy image on the limits of the printed page.

3. Although not present in this poem, the same confusion occurs when epigraphs are used. In ‘pipiwai’, for example, the epigraph appears directly under the ruled-off title, and includes, in brackets, its own translation. Further translation of other terms used in the poem appear at the end of the poem. What is the poem, then, if it can’t stand without these crutches, imprisoned by these fences?

The final poem was about death, too. Death, seen as a universal destination, that requires a lessening of faculties as words devolve to whimper. ‘Nough said.

Ultimately, I’m left with these impressions: dis-ordered, jagged words that attack rather than understand, and a sense of a poet who, though familiar with three different cultures, no longer feels entirely at home in any one of them.

Author: Vaughan Rapatahana

Publisher: erbacce-press, Liverpool, U.K.

ISBN: 978-1-907878-91-6

RRP: NZ$17.50; US$12.75, UK£9.95

Available: http://erbacce-press.webeden.co.uk/vaughan-rapatahana/4593968366

RSS Feed

RSS Feed