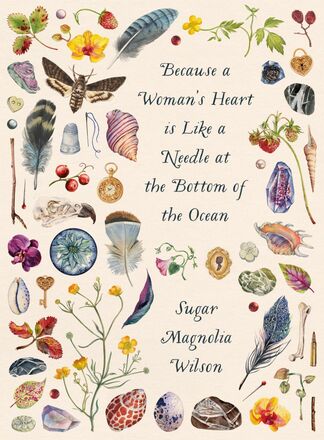

by Sugar Magnolia Wilson

This is poetry of possible worlds: time, personality and place swirl around like smoke coming from a genie’s bottle. was and could have been intermingle with I am and I might be, and we have a hard time figuring out who “I” is at any given moment (assuming we need to).

Look at the title, for starters: Is a woman’s heart really bright and sharp, lying where no one can find it until they are pricked by it? or are we talking about a classic tai chi move designed to send an opponent off balance without shedding blood?

Other times, the two worlds face off against each other, as in ‘Conversation with my boyfriend’ (pp 20-21), two poems called ‘English into [in hangul: Korean]’ and ‘[Korean] into English’:

Sleeping, you dream of a field of red cabbages. I am in the long dry lines

between the rows wearing wooden sandals and talking with your mother who

speaks to me in circles and squares, which I use to cut and gather crisp leaves

into urns.

On the opposite page is:

In sleep, I dream of the red cabbage fields, discarded urns, and you cutting my

mother’s spicy talk and hanging it on long drying lines between the rows of

vegetables. You bend down to supplant the cabbages with small strawberry

plants.

Just the same, only different.

‘The sleep of trees’ (pp 53-55) is a lullaby? a meditation? which travels from one persona to a different one, beginning:

I photosynthesise in the half-light ...

small boats upon the light

they carry sugars to feed the

birds in my hair...

The world slowly changes, using words that might apply to both trees and people, keeping us thinking ‘tree’ until:

But this is not the sleep of trees this

is the sleep of

horse and foal, always awake to the tune

of the wolf ...

and, finally, this is the sleep of mothers.

The suites of poems ‘Dear sister’ and ‘Pen pal’ begin and end the collection. They give us a panorama of worlds that play off each other, abridge each other, and contrast with each other – but all within a believable emotional framework. Where the original impetus comes from, we don’t know, although the sixth ‘Dear Sister’ poem (p 6) names the dream horse Lilith and the poet goes on to say:

We ride a lot at night. ... The night is a strange tune. Past the hustle of elm,

and there she is, Lilith, far from the Red Sea, a night creature without capacity

for fear. A breeder of demons? No. She gives me strength. ... [And]we are

home, stabled and in bed before the new day reminds the robin and the

redstart they exist. It’s a secret work we do.

The ‘Pen pal’ sequence is equally surreal. Part 3 (p 62) starts out:

Halleluiah, konnichiwa and

jumbo.

There is a tortoise that has

a broken shell and I

want to climb into the TV

and kiss it on the face. ...

and in Part 4:

This letter is in a terrible way –

knows no end.

She (Mum) is a skellington of

nothingness: shardy bones,

spider webs, a small

tortoise with a broken shell. ...

So where in the world is this all coming from? you ask. And which world? We all start out with a private world – then gradually assemble a public world of our own – but these poems go considerably farther. They seem to take their inspiration from the boundary world, the constantly shifting boundary between public and private that’s the basis for our social-media and gaming worlds. Magical realism makes sense here, as does the ability to hop from persona to persona.

And how should we deal with the poet of these worlds? Not leave her starving in a garret, that’s for sure. In ‘Pup art’ (p 31) Wilson might be giving us an suggestion:

Before she floats any higher you

hurl a net over her body, peg

the twine taut to the lawn

so she is suspended against

the pull of space.

– THIS IS ART! – you proclaim

your arms goalposts through

which only silence flies. ...

Or maybe let her fly free – depends where you’re coming from, perhaps, but this is a rich and lively collection, well worth reading in whichever world you inhabit.

Author: Sugar Magnolia Wilson

Publisher: Auckland University Press

ISBN: 9781869408909

RRP: $24.99

Available: bookshops

RSS Feed

RSS Feed