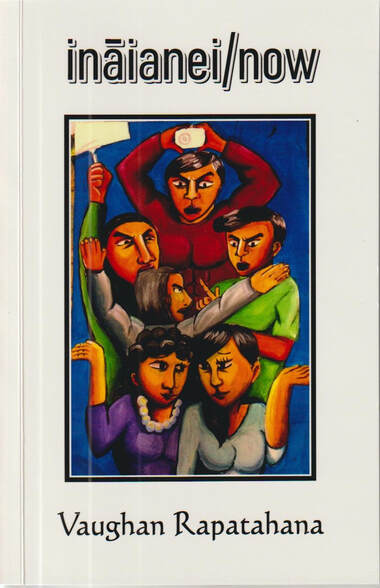

by Vaughan Rapatahana

This multilingual assemblage comes together very much like a position paper. The author looks at relationships, places, the histories and tragedies of this land, and emotions and ideas.

The poems are in Te Reo Māori (generally with English version provided) and in English, with sprinklings of Mandarin and Tagalog; the last part of the book contains an increasing number of concrete poems. In each section, the author’s voice very clearly states what he thinks now, today, in view of what is going on now, today.

The relationships speak of old loss, just as painful now as when it first occurred, and the poem ‘invictus redux’ (pp 15-16, quoted in full) seems to speak for the collection as a whole:

this was your favourite verse.

something I did not know

until later.

far too late.

your life

revoked its rhythm

rescinded its rhyme,

would never reach

crescendo.

we became fissured.

not masters of our fates

nor captains of our souls.

the kōrero we never had

the mokopuna we never shared

our future time together

a speculative fiction.

now only words remain.

a brusque poem

on bulimic paper,

wrenched from an aged book

lorn in a hick town library

no one remembers

but me.

The third section (and parts of the second) contains much more anger – as well as more Te Reo – and is very much in tune with the idea of ‘now’: the history and tragedies of this land stands out, reinforcing the belated moves to teach a corrected account of 19th century history to New Zealanders.

With a multilingual poet, it’s always a temptation – though no proof is possible, I suppose – to wonder why they are pushed towards one language rather than another for a particular poem. In this section, there are more Te Reo poems than elsewhere in the book, and the outrage seems to grow in the same proportion.

Early on (‘he parekura: Ōrākau 1864’, pp 81-84), Rapatahana quotes the New Zealand Herald’s 1864 casual description of slaughtered women and children, describing his visit to the site with the refrain

does anyone know what happened there?

does anyone care?

In this poem, he includes Te Reo in direct quotes. In the next poem, ‘te korekore tonu’ (pp 85-86), the whole poem is in Te Reo. Pages later, he is insistent that speakers of both languages listen to him equally, and his format changes to two languages side by side in columns (though I’m unable to compare meanings for both). ‘so the theft continues/na reira ka haere tonu te tāhae’ points the finger in no uncertain terms:

so the theft continues

–less manifest this

time around–

but still white fingers

in the cake, eh

poking, ever poking

into the core

while licking off the

icing.

In the final section, emotions and ideas, the poet reaches into his memory for other feelings, to accompany (but not replace or erase) the anger. The wisdom of a long life speaks (‘coloratura’, pp 130-131):

be kind to your younger self.

they did not know.

be forgiving

of their foolish acts.

...

love

who you once were.

be generous

to that former self,

in a coloratura

to that unversed mimic

no longer gazing back

from the mirror.

Interestingly, this last section is very heavy on concrete poems. Perhaps this a hint that words themselves are not enough – that where they sit and what shape they take is just as important as grabbing handfuls out of the dictionary, whichever language we choose.

here to edit.

Author: Vaughan Rapatahana

Publisher: Cyberwit, Allahabad, India

ISBN: 978-81-8253-774-3

RRP: NZ$27.00, US$18 +p&p

Available: from the publisher http://www.cyberwit.net

and from Amazon

RSS Feed

RSS Feed