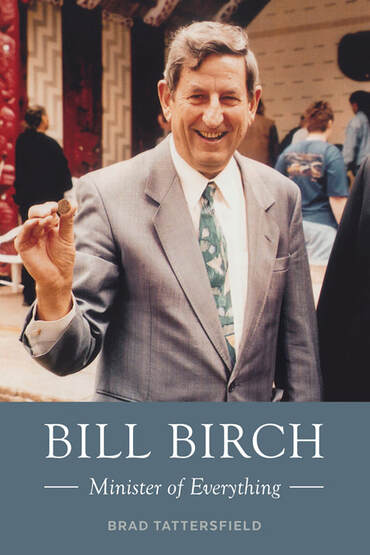

by Brad Tattersfield

Is this a biography or not? Some recent books claiming to be written as a biography are more like political memoirs, as told to a sympathetic former staffer.

Brad Tattersfield is certainly a former staffer and an admirer, and this book is described as Bill Birch’s story. Nonetheless, the author is very even-handed when it comes to examining the political issues of the Birch era, while certain personalities in National governments do receive criticism. This is both a strength and weakness of the book. Being based largely on Bill Birch’s archives, detailed diaries, and more recent interviews, it exposes candid views of colleagues. But political enemies seem to become caricatures: Ruth Richardson as an ideologue and Winston Peters as a shameless populist; with Birch and Jim Bolger as sensible pragmatists.

In fact, with regard to economic policy in the 1990s, Richardson and Birch ended up having more continuity than change, at least on the substance of policymaking. Maybe the difference in style mattered at the time, but not in hindsight.

Tattersfield admits, late in the book, that Birch became a fiscal conservative/economic liberal through his exposure to Treasury officials over time – so even if he didn’t start as a purist, he was eventually converted. But Birch also worked officials hard, convening policy meetings after midnight. The interaction with officials, and attention to policy detail, was Birch’s strength compared with the big personalities that preceded him as finance minister. While he wanted to move away from personalised economic branding – especially ‘Rogernomics’ – he seemed to lack the salesmanship needed to sell controversial policies. But he nevertheless presided over very controversial policies, from Think Big energy policies in the early 1980s, to the 1991 industrial relations legislation, where the role of trades union were no longer recognised.

So this is the major question for the book: how did a conservative, moderate politician become identified with policies which appear to be diametrically opposed, at least philosophically, and within such a short period of time? Of course, there are many versions of the economic upheavals of the 1980s, and the polarising politics that ensued, as well as a consensus among commentators on the framework. Birch certainly accepted Richardson’s Fiscal Responsibility Act which, combined with the 1989 Reserve Bank Act, circumscribed the role of ministers and Parliament, but which also reduced the accountability of officials.

Tattersfield addresses the underlying conflict in economic approach mainly in an analysis of the Think Big projects completed in the 1980s. Some readers may not be aware of the deep energy crisis in the 1970s, and policy reactions that included the so-called ‘carless days’. The massive financial cost of Think Big was just part of the contentious policymaking. The 1984 Labour Government appear to have engaged in a fire sale of the new energy assets, even before they had really been up and running, losing billions in the process. But if this appears to have been an example of fiscal vandalism one still has to wonder why the privatisation programme continued under the 1990 National Government, despite being very unpopular.

The book is less analytical, on the whole, and more of a chronological narrative. It is easy to read if one is familiar with the political events of the time, but becomes rather disjointed as the book goes on, and especially after 1996 (when MMP is introduced). Bill Birch is rather obviously a figure associated with the previous electoral system, if not the bad old days.

Author: Brad Tattersfield

Publisher: Mary Egan Publishing

ISBN: 978-0-47350197-6

RRP: $40.00

Available: bookshops

RSS Feed

RSS Feed