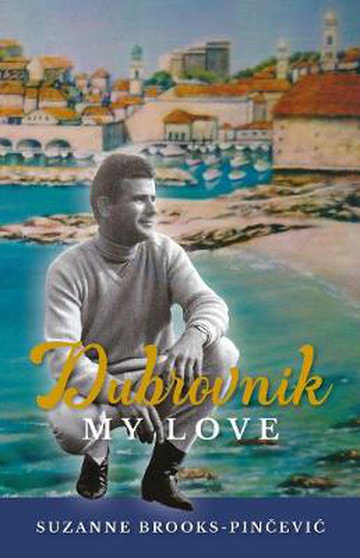

by Suzanne Brooks-Pinčević

This work of semi-biography offers a contrast, throughout, between dark and light. That is, the life experiences of some residents of a Europe only recently riven by the calamity of World War Two and condemned to live with the dark forces unleashed by it, and the light represented by their concepts of life in ‘the West’. As the central character, Gašpar, comes to realise, life is seldom painted in such shades of black and white but is much more often composed of shades of grey that vary in intensity.

At the beginning, however, his life is shaped by the constraints imposed by the political system under which he lives, the form of communism imposed by Tito’s Yugoslavia. As is the case in any authoritarian system, the glittering prizes are very much the preserve of the system’s friends and acolytes and, as a Croat, Gašpar is on the outer in a Serb-dominated Yugoslavia. This impacts on his life in ways that include education, employment, and future prospects so that he is driven to escape the tyranny that shapes his life, succeeding only by the skin of his teeth on his third attempt, an attempt that would have brought a death sentence following failure.

He relocates to Australia, and the book from then onwards outlines his adaptations to new circumstances and accommodations as he settles into a long-desired life ‘in the West’. It is here that he encounters the first shade of grey, however, as is made plain in his reaction to the migrant camp at Bonegilla: a raw and empty land of red dirt, few trees other than eucalyptus and so far inland that the sea might as well not exist. While things do improve as he moves to more salubrious accommodation and into paid employment, less obvious constraints begin to affect him. These include the attitude of Australians to ‘Dagos’ and ‘reffos’ and the presence, even within a land so far away from the source, of Yugoslav counter-intelligence, the ‘Udba’.

However insidiously, his very being as a Croat also becomes a constraint; it shapes his reactions to his long-cherished aspiration of ‘life in the West’ and is disguised, one suspects, as the book’s mention of the recurring ‘restlessness’ that drives him to change jobs and locations within Australia so frequently. This continues even after his move to New Zealand, a landscape that answers at least some of his yearning for the familiar geographies of his upbringing, and – ever so gradually – events in his homeland begin to consume him. This is evident both in his relationship with the ‘Yugoslav’ community in Auckland and in the wholesale adoption of his viewpoints by Suzette, who becomes Gašpar’s wife and who is, herself, a recent immigrant to New Zealand.

It needs to be said at this point that, despite a heavy and obvious biographical slant, this book is written as a novel and so its content ought not to be challenged on historical grounds such as the conflicting claims made for the motivations of the Ustaše in its ongoing battles with the largely artificial construct known as “Yugoslavia”.

‘Dubrovnik, My Love’ contains some extremely perceptive analyses of mid-sixties life in both Australia and New Zealand, as those fortunate enough to have lived through those times and experiences as immigrants will doubtless attest. Both societies were raw, unsophisticated and constrained by geographical position in what was virtually a pre-television age, so that levels of sophistication familiar to Europeans in food, drink, dress and social intercourse was definitely not familiar to the indigenous despite the numbers of returned servicemen who had seen some of each.

Paradoxically, both nations subscribed to the sanctity of individual rights and the inviolate nature of freedom of expression; yet both societies enforced a conformity of behaviour, ideals, and dress that was no less intense for being informal and ‘understood’ rather than nailed to anyone’s wall.

Technically, the book has some egregious flaws that derive from indifferent proof-editing and/or spelling, and the first of these concerns the use throughout of “immigrate” where correct usage calls for “emigrate”. There are anachronisms, most notably the phrases “totally out of our comfort zone” and “a large learning curve” which belong to 2019 rather than 1965, as does the grab-bag word “awesome”. Finally, it was rather odd of Suzette to explain to a recent arrival in New Zealand what ‘manuka’ is without doing the same for ‘bach’; the more so as Kiwis themselves call a seaside cabin different things according to which island they live in . . .

Author: Suzanne Brooks-Pinčević

Publisher: Leon Publications

ISBN: 9780473466565

RRP: $34.99

Available: bookshops

RSS Feed

RSS Feed