Vaughan Rapatahana

Whatever happened to untamed, un-Agent-filtered, un-English-language-obliged literature? It’s here. Little book, great leap-in-the-right-direction.

Splendidly, it starts with a quadruple battery against the tyranny of English and pleas for a Te Reo/Māori readership:

an introductory poem (‘Stay alive/I give you a book in Te Reo/Māori/open your eyes/open your ears ...’);

a Lachmann quotation (‘There is no direct substitution of one language for another ... different languages express a different way of seeing the world’);

an Introduction (‘I now write in my first language ... because I want to fully express everything in my mind, my heart, in my soul ... The English language is crammed full of the subject matter and cultural customs of the lands of Britain ...’);

and an in-your-face first poem (‘Fuck/I can’t exist in this language any more/it defeats me ... give me an escape from this prison of English’).

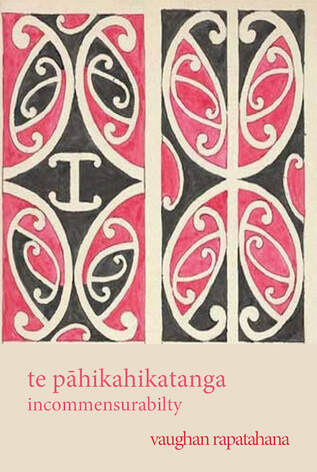

What follows is 120 pages of Te Reo poems, with accompanying ‘versions’ in English. ‘I have translated these poems into the English language, but not in a ‘perfect’ translation. It’s impossible! Thus the title of Incommensurability /te pāhikahikatanga’.

Readers who know and have followed Vaughan Rapatahana’s poetry, through, for example, ‘ternion’, ‘ngā whakamatuatanga/interludes’, and ‘ināianei/now’, will recognise much of the contents – love poems (‘ki te tūāraki’, ‘he ruri ngāwari’, ‘he papakupu o aroha’ ‘kua tekau ngā tau tonu’), poems of mourning for a lost son and broken families (‘kāore he mātāmua’, ‘ko taku whanāu’, ‘te ngākau pōuri o te huaketo’), poems of belonging (VR lives variously in Aotearoa, Hong Kong SAR and the Philippines) (‘āe te henga’, ‘te taiao Aotearoa’, ‘ko aotearoa’, ‘Orongomai’, ko taku whare tēnei’), what might be called ‘nature’ poems, with their enviromental edge (‘ngā wāna’, ‘ngā rākau’, ‘he mōtaeatea: huringa āhuarangi’) ...

but always, and amongst, lie the explosions of anger and independence that mark the committance to a language, culture and way of seeing that has been overborne, murdered, ignored, sidelined, snuffed out, embraced-so-as-to-suffocate, and had its history distorted and hushed.

We read, we wait, and we get ... at p.44 comes a gentle claim for Māori ‘ownership’ (‘aotearoa ... a normal name before an abnormal name/a first people before strangers’); in ‘kerikeri’ urgency and injustice grow (‘ignore the words of this white person/it’s time to get real for some white people/real like the original inhabitants of this town’); in ‘ko te tāima mō he panoni nui’ the consequences of white culture’s/language’s take-over are laid out (‘there are many youths suiciding/too many Māori youths/it is time for new thoughts’); pleas for Te Reo in ‘ngā ruri Māori (‘where’s our Māori poems/where’s our words?/not here/not here’) and ‘e pīkau ana ahau he riri’; and in ‘Rangiaowhia, 1864’ (‘who knows about the murders at Rangiaowhia?/the terrible deed of the pākehā/the massacre by the white men/we all should know’) and ‘te pakanga nui o waikato anō?’ (‘rangiriri, rangiaowhia, ōrākau/who knows about these?’) the naked facts of a history tidied away crackle onto the pages.

As it began, the collection ends with a section of ‘notes’ that contain a fourfold battery on the dominance of English. First, a rational exposition of translating his own poetry into English, reluctant but unavoidable in many ways (‘The ‘solution’? To write in one’s indigenous language as much as practicable and to hope, to expect, that readers and listeners aspire to learn it too ...’); followed by a poem oringally written in English that also ‘critiqued this tongue’ – ‘tongues’ (p.127)

no one around here speaks english.

not because they cannot

but because they don’t need to.

This is a many-levelled poem that tackles the issue forthrightly: clearly VR knows ‘other languages’ (and other languages than English and Māori) – there is no excuse for us.

The third concluding shot is ‘aroha mai, apirana’, in which ‘Everything I have been saying, then, is summarised in the final poem’ –

let’s murder this marauder once and for all

ko mate, mate, mate me kāore he ora mō tēnei arero

and finally, the personal struggle, every day, to ‘supplicate its fancy frissons/into brute submission’ (it’s being English’s) and the smiling note

today i maybe

won

It is not, however, the wholly admirable fighting of a good fight, that makes ‘te pāhikahikatanga’ such an important and beautiful collection: it is the telling mix of the personal and the public, the different sorrows and contentments, explosions that are not only political but also from daily life, gentleness and humour (even in the combative poems), and the final feeling, to an English reader/speaker, that they are not the rule of thought, expression, feeling, culture and awareness, nor of the expression of these in poetry – that there is a whole world of other people going about their writing and their lives unfiltered by that most awful of literary Agents – the English language.

screw the flag of England ...

a big bare-arse to this flag

two fingers to this symbol

of injustice...

I want a flag

for all the people

of Aotearoa.

Author: Vaughan Rapatahana

Publisher: Flying Islands Books, Australia

ISBN: 978-0-6455503-3-7

RRP: $10

Available: https://flyingislandspocketpoets.com.au/product/te-pahikahikatanga-incommensurabilty-by-vaughan-rapatahana/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed