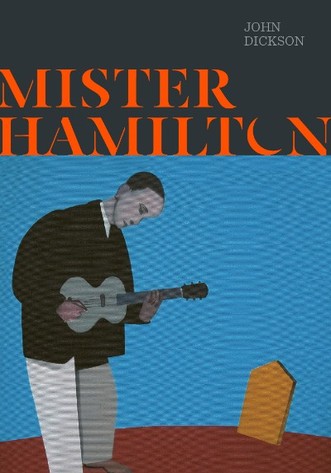

by John Dickson

This is the first collection of poems from John Dickson in eighteen years, and it is worth the wait. Personally, I’m all for slow growth, and if there was ever a profession that required long and deep contemplation, it is probably that of poet.

The twin virtues of what constitutes good writing, in my opinion, are clarity and flow. They allow for readability, and that is something I look for rather than the more difficult to define ‘literary merit’. John Dickson’s poems have both.

I still relate well to clarity and flow in poetry, along with that added and indefinable ‘something’ that declares it to be poetry and not prose.

Too many amateur poets believe that a poem is delivered by an ethereal muse, fully formed; that they are merely the scribe who puts the words down on the page – “That’s exactly how it came to me!” they cry, and pause expectantly, awaiting praise.

The analogy in my mind to this approach to the making of poetry is as if I were to declare my intention to make a chair, throw a pile of sticks upon the floor, and invite you to sit down. What a blessing then to explore poems by a man who understands his craft.

No one can accuse him of being hasty, or anything but thorough in the creating of best words in best order. Throughout, his pace seems unhurried, though always varied to match the intent of the poem. The rhythms are mostly conversational, and he acknowledges this in his notes: “In producing Mister Hamilton I attempted to compose verses that would not only use the speech rhythms of other people as well as myself, but also match the rhythms with various metrical patterns. (Yes, indeed, tick tock, tick tock, or the challenge of timing.”

Slow writing, and slow reading for this reviewer; and there is plenty of meat to savour on these finely-sculpted bones.

‘Plainsong,’ a favourite, clearly acknowledges the differing patterns and tonalities of region:

“… I am from Southland.

Some people say my speech is slow

I say it’s deliberate, just.

And my soul runs dark

like Southland’s slow intestinal rivers…”

There is story in his poems, too, even in something as contained as ‘The light above his head’ and the man writing a poem on the beauty of granite, or ‘Dee Street, Invercargill, 1960’ with its focused observation.

The longer poems are challenging. I needed the notes at the end, and did some Googling to fully understand them – if one ever can fully understand another person’s sharing of thought and emotion in poetry or prose. After careful study of the first, ‘The persistence of football results on Beasley Ave,’ I was rewarded for being a slow reader with a run of poems by Dickson that were shorter and yet still acute.

‘Piano time with Monk’ resonated with this lover of jazz, and its defence of response without explanation – to listen, to react, instead of standing apart from the music to construct a critique. To allow the music to take us where it will is always better than wallowing in theory, though the theorists also have their role to play, I’m sure.

‘Question’ tells us that “In middle age, the laws of living become slowly clear,” and that word slowly is how I continued to approach these poems by Dickson.

(I have sent a copy of ‘This is Zepf’s poem almost word for word’ to a writer-friend who, like me, favours clarity and flow, but who is also a dedicated football coach. He’ll get it, I know.)

I resisted ‘Something else’ at first. What was a chunk of prose doing in a book claiming to be poetry? Somewhere at the back of my mind lurks the word ‘proem’ to describe this kind of writing. In the end I accepted it as it was offered – a deeply felt weaving of various strands of narrative centred around the grief of losing a child. Subtly the point is made that TV brings too many reports of dark events worldwide that we cannot fully comprehend or fight against. There is reference to Brueghel’s equally complex world, the surface busyness, the dolorous undertones – “the mute song of unnameable blackness” – and a father mourning his dead daughter.

As in a ‘Road near meremere’ others have mourned such losses, marked by:

“No roses

no thorns

four crosses nailed to a pole.”

The careless, reckless deaths upon our roads.

If life is transient, as we know it is, let us all slow down, so as to mark it more clearly, Study it more nearly, beginning to grasp that we’re trying to understand what may never be fully understandable, like the secrets the dead take with them to their graves.

Mister Hamilton is a collection of poems of a thoughtful man, compassionate and also dispassionate, which sits well with me. I dislike the unkempt outpourings some writers pass of as ‘inspired by the muse.’ (Someone should shoot that dratted muse.)

In writing, intellect must control emotion, not be overtaken by it. How else are we to allow readers the courtesy of bringing into that space we’ve left for them their own knowing of loss and pain and grief and occasional miscomprehensions? Done that. Been there. Thank you for sharing with me, poet.

Dickson says:

“… now I’m sixty-five

and approaching silence,

when I listen to someone

telling their thoughts

of that and this,

I nod and smile

all the time thinking,

The minutes,

the minutes do go on.”

When a poet of the calibre of John Dickson speaks, it’s good to listen, and ignore the minutes ticking by, caught, for now, in his silver net of words.

I’m presently commissioned to write an article on love poems, so let me end with some of those words from ‘Fourteen lines for Jen.’ I equate them with Yeats’ “one man loved the pilgrim soul in you” .

Dickson says:

“… when I think of

how much I love you, the flow of my blood

sings the nomadic song of a summer sleep.”

Let all our poets write so slow and deep.

Author: John Dickson

Publisher: Auckland University Press

ISBN: 978 1 86940 855 8

RRP: $24.99

Available: bookshops

RSS Feed

RSS Feed